Why Laurie Halse Anderson’s “Shout” is a memoir worth talking about

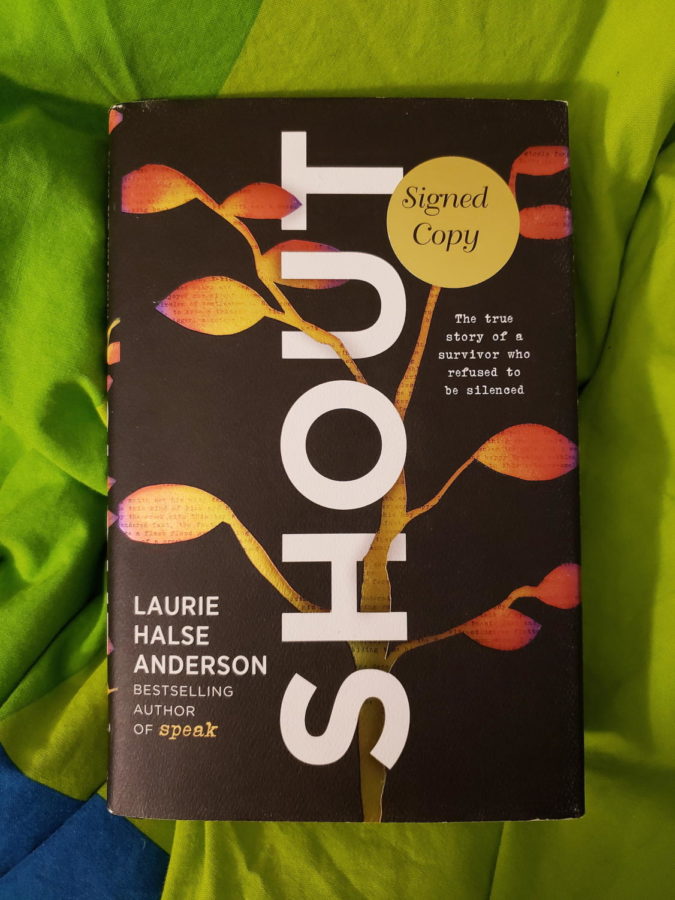

“Shout” by Laurie Halse Anderson, a memoir on surviving sexual assault and refusing to be silent about it.

November 8, 2019

Laurie Halse Anderson’s novel “Speak,” published in 1999, follows the story of Melinda, a freshman in high school, as she deals with the trauma of her sexual assault. The book became an important voice in Young Adult literature, encouraging teenagers to speak up about their own sexual assault, and demonstrating to people both young and old about the power behind using your voice. Anderson contributed in opening the door for discussions about sexual violence, and her newest memoir “Shout,” which was published in March of this year, continues the conversation.

Fueled in part by the criticism of the #MeToo movement started by Tarana Burke in 2006, Anderson started writing “Shout” as a vessel for her anger. The book is written entirely in verse poetry form, which Anderson said allowed for a more “visceral experience” in a BookPage interview, and is split into three parts. The first recounts Anderson’s experience of being raped at 13-years-old, and the long-lasting repercussions of it (“Rape wounds deeply, splits open / your core with shrapnel”). She discusses her struggle with drugs and staying focussed in school, and how she found solace in sports and books (“the only thing that helped / me breathe / was opening a book / mist enveloping, welcoming”). Eventually she travelled to Denmark as a foreign exchange student, and it was there where she truly reset herself, “rinsed out my brainpan / with salt water from the North Sea / and so began my next life”.

The second part is about her audience’s response to “Speak”; she tells of the girls and boys who came up to her during signings and after speeches, who spoke to her about their own experiences with rape. She writes about her struggle with schools who refused to let their students read “Speak,” who cited “inappropriate content” as the reason. In one poem, she talks about the librarian who wanted to order the book but couldn’t risk losing her job. In another, she remembers the principle who set off the fire alarm to cut her talk short.

Stigma around sexual violence prevents people from talking about it. It is with this book that Anderson encourages the young to fight that stigma, to hold each other up, to talk. Talk to each other, talk about what happened, talk about what you can do. And she reminds the older to listen, to really pay attention to what they have to say. In one poem, Anderson describes a man who had worked on the movie for “Speak.” He was a “big square guy, / head like a paint can, / hands the size of catchers’ mitts, / smelled like work.” She recalls how he talked to her, revealed that he was just like Melinda, how a lot of them working on the film were like her, because—”he blinked and the tears escaped— / ‘it happened to us, too.’”

When people aren’t allowed to talk about it, they become trapped, stagnant in their trauma. “If you don’t [talk about it], people don’t realize how real it is,” said Allison Budianto, a junior. “And then how will they believe it?”

Junior Angela Reyes agreed, saying “If you don’t talk about it, then why should people believe it’s a real thing?”

It is only with communication and an open mind that learning can happen. And when learning happens, so does change.

As Anderson said in a Bookish interview, “I no longer want to just open the door. I want to rip it off its hinges.”